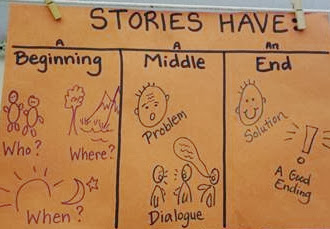

Rosa Parks teacher Brook Pessin-Whedbee teaches kindergartners how to tell stories

Brook Pessin-Whedbee teaches five-year-olds at Rosa Parks. I teach law students in their mid-20s. As a kindergarten teacher, Brook teaches her students how to collaborate in the telling of stories, so they develop not only oral language and story writing skills but also the ability to form partnerships and work together. As a clinical law professor training and supervising law students in the complex representation of clients facing the death penalty, I teach my students how to collaborate in the telling of stories — stories of our clients’ lives, of unfair trials, of prosecutorial misconduct, etc. Brook and I have the same goals: to improve our students’ oral and written skills, and to teach them what it means to work productively as part of a team.

Brook recently wrote a blog post about the work she has been doing as part of the Mills Teacher Scholars program to improve her practice as a teacher, specifically related to teaching kindergartners how to collaborate in the telling of stories. I saw Brook present about her inquiry as part of a showcase last year, and I was immediately struck by two things: first, as a fellow educator, that Brook’s pedagogic inquiry related directly to my own teaching of adult learners; and second, as a parent, that it was enlightening and somewhat thrilling to see teachers in the Berkeley public schools make productive use of real-time classroom data to inform their instruction.

We hear a lot about data these days, and there are benefits to crude data (like the results of an annual standardized test such as the CST) in terms of spotlighting racial and socio-economic disparities in student achievement generally. But parents like to think, and they deserve to know, that their children’s teachers are continually and consistently assessing their learning, not just to demonstrate overall trends in the school or the district, but in order to help their children learn and grow. But when we think of assessments, we think of tests; and when we think of data, we think of test results. Brook’s data, in contrast, consisted of video of her students interacting; their written work; conversations she observed between students; and conversations she initiated with students. As she writes, reviewing this data and sharing it with teacher colleagues in a collaborative inquiry has made her a better teacher:

[T]hrough collecting and analyzing authentic data from the students in my classroom, my teaching practice has deepened. From slowing down and zooming in on their process, I have learned to notice patterns in the partnerships and to adjust my teaching to facilitate more collaborative relationships. I have learned that it’s ok for partners to struggle, to stick with a difficult pairing and to do the hard work of learning how to work together.

This is an example of teaching students important skills that simply cannot be tested. There is no standardized test that can measure Brook’s students’ ability to collaborate. Yet this is a critical life skill, one that my colleagues and I are still teaching to our law students, decades after they’ve graduated from kindergarten.

Read Brook’s post if you have a few minutes. Whether you are a parent or an educator, I think you will find it inspiring.

cation skills, and being a good team player are just a few of the benefits research shows music, foreign language and physical education have on a developing mind.”

cation skills, and being a good team player are just a few of the benefits research shows music, foreign language and physical education have on a developing mind.”

She eventually became disillusioned with punitive measures that weakened public schools, narrowed curricular offerings, and failed to achieve equity in educational opportunities and outcomes. She is now one the most visible national advocates for public education, and certainly the most vocal national critic of our current high-stakes standardized testing culture.

She eventually became disillusioned with punitive measures that weakened public schools, narrowed curricular offerings, and failed to achieve equity in educational opportunities and outcomes. She is now one the most visible national advocates for public education, and certainly the most vocal national critic of our current high-stakes standardized testing culture.